CX Reconsidered [2]: MVVM to the Rescue

Tactical implementation of the MVVM pattern will stop CX constructs bleeding through all of your code. In the first installment of this series, I have argued that CX data and threading structures tend to proliferate throughout your program, and that this is both unlike advised & advertised by Microsoft and undesirable because it drives out the far better developed C++ constructs. What we need is development tactics that keep the CX layer as thin as possible. This blog post presents first steps in the development of such tactics aka software development patterns or practices.

The goal is that:

- CX is used within specific layers of the design of a program.

- Each CX layer has a very limited set responsibilities.

- CX can be put to good use for the assigned responsibilities.

This is the second blog post in a series of n about my experiences with CX, and how I intend to use it in working with C++ and Xaml in the context of Windows 8.The table of contents into that series can be found in the first article in this series.

Ok, at the end of part [1] I wrote that next up would be a review of a number of (heated) discussions around the introduction of CX. But I changed my mind. It seems to me that although there is definitely value in a well argued position, there is more value in a working solution. So, let’s take a look at a way to put CX at its proper place.

Advised & Advertised CX Usage Policy

The usage policy for CX is, according to MS employees and documentation, to limit the use of CX to a thin layer at the ABI boundary. See e.g. the first response of Herb Sutter in the discussion after this Build 2011 talk

[ABI: At the lowest level, the Windows Runtime consists of an application binary interface (ABI). The ABI is a binary contract that makes Windows Runtime APIs accessible to multiple programming languages such as JavaScript, the .NET languages, and Microsoft Visual C++. (from the Hilo documentation)]

So, when we are interacting with the environment of a Windows Store application or component, we have to deal with the ABI.

However, there is nothing inherent to CX to enforce the advised & advertised usage policy. In part [1] of this series, it has been argued that it is very hard to ‘escape’ from CX and to restrict CX to a thin ABI interface layer.

The main reason it is hard to escape CX is the approach to developing a native code program that is natural to Visual Studio. This approach is a copy of the approach to developing .Net applications. You choose a project template, which assigns a central position to the user interface, then you add functionality to the program, extending, so to say, the capabilities of the user interface. For Windows 8, MS has introduced this approach also for native code, and they call it working with C++/CX. Point is, it is not C++ at all. Note also that CX is far, far behind to .Net in its development.

Nonetheless, if you start development with a CX Visual Studio project, it is CX that is used to interact with WinRT, and it thus defines the interface to the environment of the program. Because CX defines the periphery of an application, a tendency arises to define the main data structures in CX as well as considering its execution thread, the UI thread, as the main flow of control. We tend to consider the UI thread as the main flow of control because today’s apps are typically architected to react to events in the application’s environment. A consequence of this design is that CX language constructs and data structures tend to proliferate throughout a program, to bleed through all of your code. This proliferation generates a number of problems:

- Non portable code. The code cannot be compiled with a non-MS compiler, hence is not fit for use on e.g. IOS or Android platforms.

- It drives out the far more developed and richer C++11 language constructs, idioms and data structures.

- It drives out the far better .Net developer experience, if we consider CX to be positioned as a native alternative to C# .Net.

So, since CX does not itself enforce the Advised and Advertised Usage Policy of confining CX to a thin ABI interface layer, it is the CX user that carries the burden.

As a CX user, you will need a software pattern that restricts CX to what it is good at (yes, it does have its strengths), and to locations where it is useful. Such restrictions can, of course, be realized by disciplined application of conventions, but here we strive to have structural constructs that support the desired restriction: structural constructs that put a definite end to CX proliferation.

In restricting the use of CX we assume the task to not define the main data structures in CX, and to not run the principle flow of control in CX. We are constructing a generally applicable, patterned approach to developing programs involving one thin ABI interface layer of CX.

Overview of the Solution

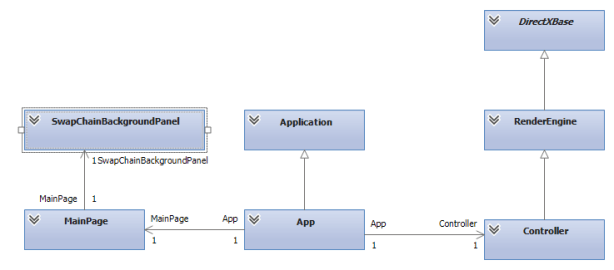

In this blog post we propose to implement MVVM as a double layered structure, as depicted in the diagram 1. Yes, layers can be expressed as rectangles (with rounded corners, even) as well.

|

Diagram 1

As you can see, the core is considered the most important part of an application :-).

Components

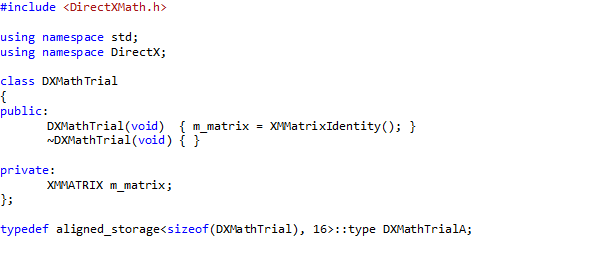

In terms of physical components, or types of Visual Studio projects, or types of MS technologies, the proposal is to implement the core in C++, as a static library (or several static libraries); to implement the Interface as a WinRT Runtime Component written in CX; and to define the User Interface in Xaml with ‘code behind’ and other environmental interactions in preferably in C# or, if the situation necessitates the use of native code, in CX.

MVVM

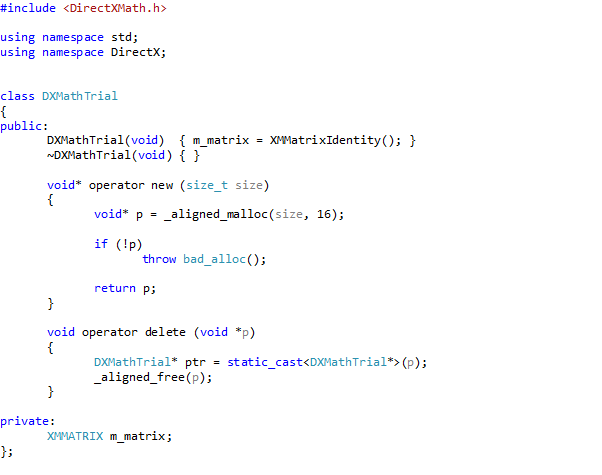

The Model – View – ViewModel pattern will be used to stop the bleeding of CX constructs. Diagram 2 shows an image from the PRISM documentation that provides a very clear idea of the MVVM pattern.

Diagram 2: PRISM interpretation of MVVM

In this article we will use a slight variation of MVVM: We consider the View to cover all of the environmental interactions, not just the GUI.

The MVVM pattern is tactically implemented as follows:

- The View is realized in the Peripheral layer.

- The ViewModel is realized in the Core layer.

- The Model is also realized in the Core layer.

The Interface in Diagram 1 doesn’t have a specific role in the MVVM pattern, it has an implementational role.

Should you like to review the MVVM pattern, you might like to take a look at PRISM or the MVVM Light Toolkit (the historical roots of MVVM are really interesting as well).

The Peripheral Layer

Conforming to MVVM, we keep the Peripheral Layer as thin as possible. There are many different types of environmental interactions, which for now will be conveniently categorized as “The Xaml UI”, and “Other types of Environmental Interactions”.

The Xaml UI

There is always the discussion of how much code to allow in the code behind of an MVVM implementation. Since we really want layers that could contain CX to be thin, we decide two things:

- We use as little code in the user interface as possible. We limit the View to presenting data to the user, sending Commands and data to the ViewModel, and responding to events (callbacks) coming from the ViewModel. On the other hand, we allow code that defines interactions between user interface elements only. An example of the latter is opening a file picker when a user has clicked a button.

- We make the boundary between the Views on the one hand, and the ViewModels and Models on the other hand an ABI boundary.

Why an ABI boundary between View and ViewModel?

Well:

- For data binding and commanding. Any object exposed by a Windows Runtime Component across the ABI to a C# Xaml UI can be a source for data binding (this holds for C#, but not for CX).

- As a containment barrier in case a Xaml + CX GUI is used.

CX is Not a Good Choice For Xaml UI Code Behind

But that may change over time, of course, so let’s pin it down to “in august 2013”. So what’s wrong with the use of CX in the code behind of a Xaml UI?

- Data binding support is rather crude. Data binding in CX requires data binding source classes either to be decorated with the Bindable attribute or implement ICustomPropertyProvider, and have the bindable properties registered as ICustomProperties (see Nish Sivakumar’s implementation). Either requirement makes it extremely impractical (I would like to have written ‘impossible’ here) to data bind to properties exposed by a Windows Runtime Component. So, note that by requiring an ABI barrier between the UI and the ViewModel, we virtually ruled out CX as a possible language for Xaml code behind.

- MVVM support is unstable. I have defined several (non trivial) Xaml GUIs with CX as code behind platform, and seen the Xaml designer crash when a ViewModel locater class was inserted as a global resource to provide the DataContext and also data templates were provided to it as resources. On incidental beautifully sunny days the designer would provide an error message saying it could not instantiate some resource.

- Asynchronism: the PPL tasks library seems to have a special version for Windows Store applications, and it is rather hard to handle. It also frequently seems to operate not according to its documentation.

An argument to do use native code is performance. But we intend to keep the Views layer a thin layer, with an absolute minimum of functionality, so the performance of this layer will not easily affect general program performance. This is both because it is a minimal layer, and because it is the UI, i.e. it is about sending data about user actions to the core.

So, the performance argument has relatively little weight, and I think we are better off using C# .Net in the Views layer. Just because it supports development so much better. Think e.g. of the support for MVVM itself; there are several, and leading, MVVM frameworks to support you using the pattern for applications of arbitrary complexity.

When using C# in the code behind, one thing we do have to pay attention to though, is marshalling data across the ABI. We want data that crosses the ABI to be copied only if unavoidable or when we like to have a copy instead of the original. In general we want to have pointers (references) copied across the ABI. As we will see (elsewhere) this requires the use of write only data structures, also if we only want to read the data with which the write only data structure is initialized.

A possibly less urgent consideration is that the combination of a Xaml + C# GUI and native Windows Runtime Components is also a way to go on the Windows Phone platform.

Other Types of Environmental Interaction

The above section discusses the case for the Xaml UI – the View. How about the other types of environmental interaction mentioned, like database access, networking, file access, etc. Will you do that in .Net as well?

As a first go, yes. The peripheral layer should be minimal, so in the case of e.g. incoming network data you would like to stream incoming bytes as directly as possible into a buffer controlled by the core, as an unstructured stream of bytes. I think that we can set this up so that C# is used to control the work, but the system (written in native code) is used to do the work, hence performance will not be an issue.

If performance does turn out to be an issue (after measurements and analysis), I would use a native solution. Think of the C++ framework Casablanca, or even a custom solution in CX (indeed!).

The Core Layer

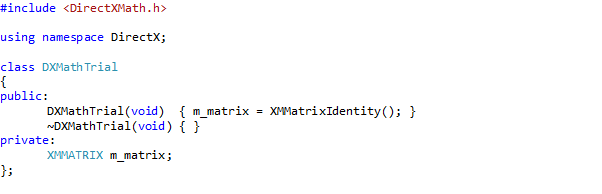

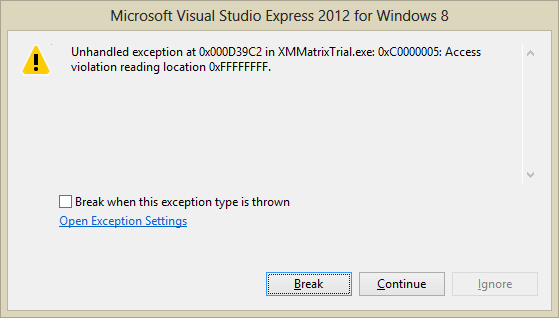

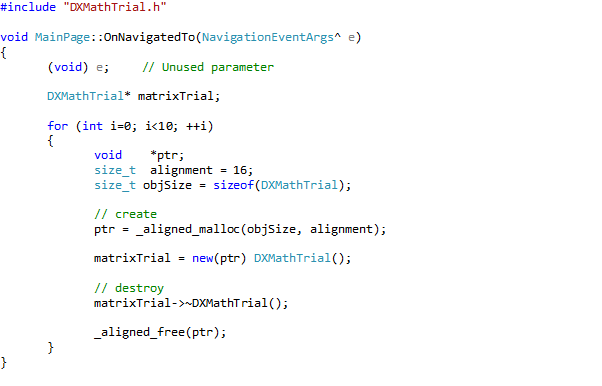

This is where we want to write static libraries of ISO C++11(+) only. Why?

C++11

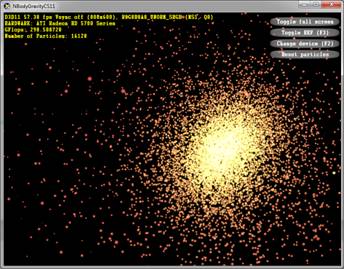

Personally I happen to like C++ (and the STL), and version 11 more than earlier versions. Apart from that, maximum performance against minimal footprint gets you the most out of available hardware, which enriches user experience and hopefully also reduces (environmentally relevant) power consumption.

ISO: Portable Code

In the second quarter of 2013, some 44.4 million tablets were sold running either iOS, Android or Windows (8), of which 1.8 million are running Windows 8. In the same period, 227.3 million phones were sold running either Android, iOS or Windows Phone (8), of which 8.7 million are running Windows. So, we want to port our precious code to Android and iOS, thus reaching a market of say 271 million devices sold in the previous quarter alone; that’s over a billion in a year :-). And then there is also the PC market, of course, of about 500 million PCs running Windows, and coming to Windows 8 sooner or later.

Library

Putting code in a separate library allows you, among others, to specify the compile switches you need for a specific piece of source code. Using a library will allow us to specify that the compiler must not compile CX: we will not set the /ZW switch (or rather, we will set it to /ZW:nostdlib). So, CX constructs cannot bleed into such a library.

Static Library vs. Dynamic Load Library

Static libraries link at compile time, not at run time, hence have a relative performance advantage. Also if you export activatable classes (COM Components such as CX classes) from a static library, they cannot be activated. From a dynamic library, they can, see here. So, CX classes cannot be run from a static library.

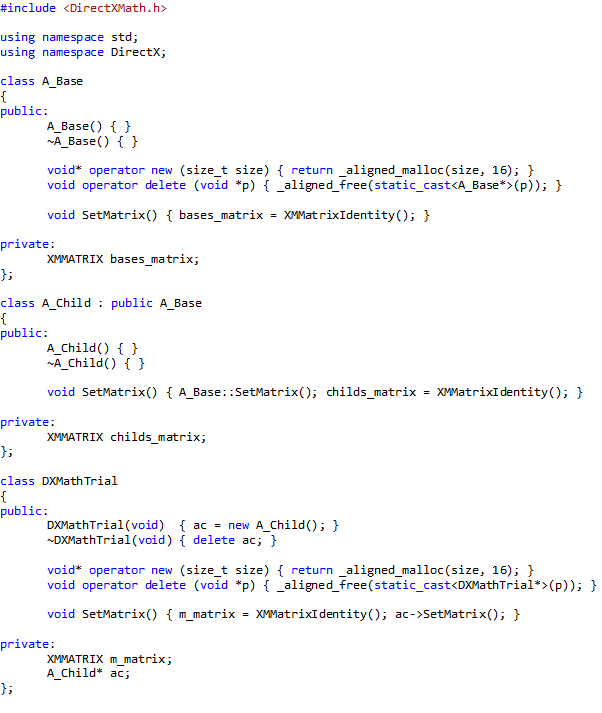

Structured Data

We will make sure all main data structures are part of the Core Library. The use of system facilities, such as data transport, will be defined inside the core by C++ constructs, such as ‘pointer to stream’, that are used by the Interface layer to import and export the required data – as streams of primitive types. So, no CX owned main data structures.

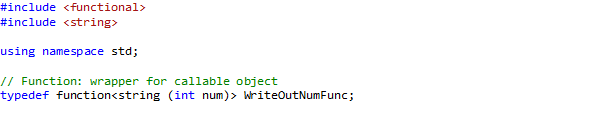

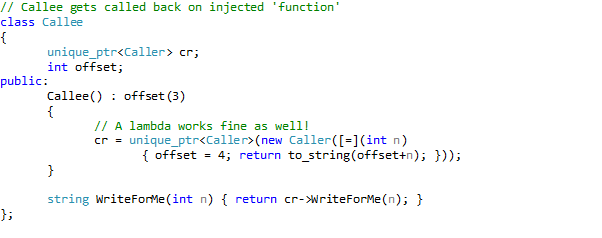

Inversion of Control and Dependency Injection

We will expose any functionality only as Inversion of Control (IoC), also known as ‘The Hollywood Principle’: Don’t call us, we’ll call you, either by Dependency Injection (DI) or a Locator Service, see e.g. the articles by Martin Fowler here and here.

If the Core runs on its own thread(s), it is not susceptible to threading issues created by interactions with the Peripheral or Interface Layers (although it might have its own threading issues). We are also in a position to use STL threading; the bleeding of Microsoft threading technology into code we wish to be portable can be halted. So, no CX owned threads in the Core.

The Core and the UI: Ownership issues

We would like the Core library to be as independent as possible. The rationale behind these tactics is that independence from CX precludes having to incorporate CX constructs, either with respect to data or with respect to control. Another advantage may be that the Core’s lifecycle is not controlled from the UI thread, hence no freezing, throttling or killing. Of course, there is also no freezing of the UI.

The core library is already really independent by incorporating the program’s main data structures, by managing its own threads, and by utilizing the IoC pattern. Nevertheless, we can take independence a step further by looking at the ownership of the Core library. Who is the owner, that is: who controls its lifecycle?

The system starts up a Xaml application by calling the main method defined in App.g.hpp (CX) or App.g.i.cs (C#), which then starts up the UI. Usually you then instantiate other classes from the principal UI classes like the App or MainPage classes.

Alternatively you could define your own main method. The Xaml main method is decorated with the DISABLE_XAML_GENERATED_MAIN symbol. If that has been defined the decorated main function will not be used (surprise!). Your main method could instantiate the Core library and provide the UI with a handle, while holding a reference itself in order to control the lifecycle of the Core. The Core and the UI are now completely independent. An example of a system with an alternative main function is the demo application in the WinRT-Wrapper library by Tomas Pecholt. See here (the comment by Tomas) for an introduction to the WinRT-Wrapper.

Less invasive tactics (which I like better) may be to provide the library with a factory that creates the core, holds ownership and provides the UI with a ref counted handle. So, there is no ownership of the Core by the UI or the Interface.

First the Core

Where C# .Net applications start development at the UI, I think development in C++ + Xaml applications should start at the Core library.

The Interface Layer

Mediating between an application and the ABI, i.e. the system, that is where CX can be valuable. The strong point of CX is that it is ‘syntactic sugar’ over WRL constructs; CX reduces the amount of code markedly compared to the WRL. The WRL (the Windows Runtime Library, an ATL analogue), is itself intended to make interactions with the Windows Runtime practical. It has been shown multiple times (see specifically the articles by James McNellis) that CX makes it much more comfortable to interact with the Windows Runtime. If so required there is nevertheless always the possibility to pass by CX and insert some WRL code as demonstrated by James McNellis (see the answer) and here, and Kenny Kerr. As I understand it, CX code is the better choice for the bulk of WinRT interfacing code, but at times, WRL is the better choice for getting the ultimate performance. See the talk and slides by Sridhar Madhugiri at Build 2013

Since this is where CX is really useful, this is the first and foremost layer we want to keep thin. The layer’s responsibilities are (only) to relay data and commands across the ABI from the Peripheral Layer to the Core, vice versa. Of course, with a minimum of copy operations. We will use it, so to speak, to map the interface of the Core Library onto the ABI.

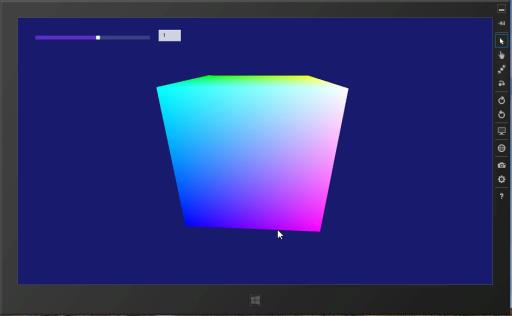

Well, that is not entirely true. Couldn’t resist the temptation to add a slider (and a data bound TextBox that shows the value) that controls the rotation speed and direction of the cube.

Well, that is not entirely true. Couldn’t resist the temptation to add a slider (and a data bound TextBox that shows the value) that controls the rotation speed and direction of the cube.